Fitting not Flitting

How young children develop and learn through ‘schemas’ or ‘repeated patterns’ a blog by Cath Arnold

My name is Cath, I am now semi-retired after working in the early years sector for almost 50 years. I began working at the Pen Green Nursery in 1988 after working in private provision for about 12 years. I had had very little in-service training or professional development during those 12 years. However, I had always been intrigued by what children did with what we offered them. So, when I was presented with the idea that children pursue biological patterns of action (schemas), this made a great deal of sense to me. I began researching to learn more from the children and their actions.

The important aspect, pointed out by Chris Athey, is that children are often not ‘flitting’ from one activity to another, as we once thought, but ‘fitting’ ideas together about how the world works (1990; 2007).

They (and we) try out an action with different materials in order to generalise about what will happen. Terms used in the research literature to describe how children learn are ‘assimilation’ and ‘accommodation’. With ‘assimilation’, the clue is in the word, so when we try out an action ‘similar’ to what we have tried before and the effect is similar, we readily take on that learning. Studying the play of individual children has been my specialism, in my MEd, PhD and 4 of the 5 books I have written. In this blog, I am focussing on Rhys, my youngest grandchild. So, when Rhys dropped something from his high chair, cot or shopping trolley and it landed below him on the floor, he expected that to happen with any objects he chose to drop, and most often, it did.

However, when he dropped a rather bouncy ball, the effect was different in that it bounced away from him. This required him to ‘take on’ or ‘accommodate’ some new learning, about trajectories.

We cannot predict what patterns each child will explore. In terms of Rhys’ explorations, as well as moving lines or ‘trajectories’, he also explored static ‘lines’ extensively as well as ‘enveloping’, ‘containing’, ‘transporting’, ‘connecting’ and different ‘positions’ such as ‘on top’. This is referred to as a ‘cluster of schemas’.

So What?

Chris Athey described these repeated patterns as ‘partial concepts’ and she and others have advised play partners to use language to articulate what children are doing. This seems to help the building of concepts. Also, offering different stuff with which to explore can result in learning eg a bouncy ball to drop from a height.

So, how do these actions develop into concepts?

Although Chris Athey referred to the development as ‘levels’, I prefer to call them ‘ways’ of exploring patterns: through our actions (‘sensori-motor’); through ‘functional-dependency’ relationships (that is, understanding what will be the consequences of an action); ‘symbolic’ (making one thing stand for another, as in role play, writing or language), and ‘thinking’ (usually, referring to something in the absence of reminders, although, my hunch is that even babies think).

When Rhys repeatedly threw his monkeys from his cot onto the floor for his Aunty to retrieve (in images below), I would say that he understood the ‘functional dependency’ relationship between his action of throwing and where the monkeys would land. He was confident at this time and ‘played’ with the idea. It became an interactive game.

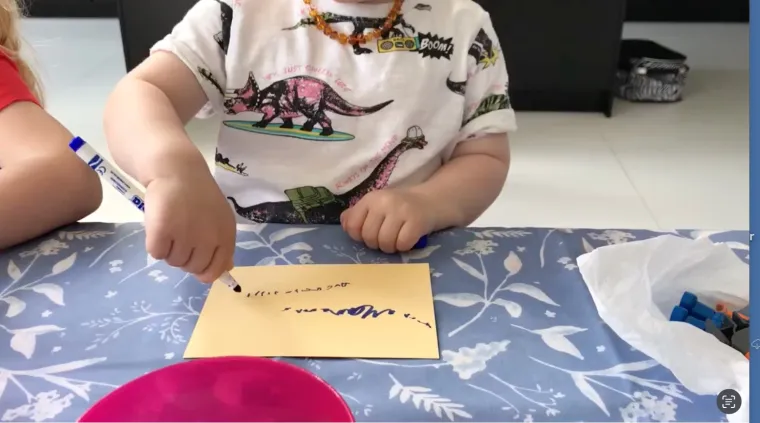

Rhys’ exploration of lines resulted in him placing marks in a line at 23 months, which is symbolic of the lines he was exploring with objects.

Rhys has played ‘connecting’ with ‘duplo’ and ‘lego’ extensively since he was very young. The first record of Rhys playing with ‘lego’ he was just 2 years old.

The best example I have of Rhys ‘thinking’ is a conversation he had at the age of 4 in the summer with his grandad:

Rhys had been showing an interest in numbers so his dad gave him a 100 square to look at.

He asked his grandad: “How old are you Pop?”

Pop “75”

Rhys looked for the number, firstly pointing at 57.

Pop “No, it’s a 7 then a 5”, at which point, Rhys found 75.

Rhys to me “How old are you Mop?”

Me “74”.

He noticed that this was next to 75, and, knowing my birthday is in October like his, he said: “You’ll be the same height as Pop when it’s your birthday!”’

This conversation showed that Rhys, after exploring lines, had a sense of the order of the months. He had an idea of ‘lived age’ but thought it resulted in everyone getting taller, which can be seen, rather than the more abstract concept of age increasing.

Rhys is now 7 years old and has the most beautiful joined up handwriting. We think, because, for several years, he has been playing extensively with sets of small lego, connecting and improving his fine motor skills.