Kerry Murphy is an early childhood specialist with a background in neurodiversity and disability. She is a lecturer in early years & SEND at Goldsmiths University, an author & student completing her EdD at Sheffield University.

Reflection on child development

Like many, when I began my training as an early childhood educator, I was introduced to well-known early childhood pioneers who provided valuable insights into how children learn and develop. I was taught that children usually progress through stages of exploration and learning, finally reaching a state of maturity in which they are school-ready. To guide my everyday practices, I would turn to child development documents that outline what to expect and when through age and stage-related milestones. Much of what I learnt was undeniably valuable and relatable to what I was observing in everyday practice, and I felt that, over time, I became a skilled child developmentalist. Until, that is, I was faced with children whose development did not fall neatly into what I had been taught would happen on their developmental pathway. At that point, I only had access to information that took a deficit view of their development. In turn, I took a deficit view and considered these children to be delayed or problematic. There were often discussions of “red flags” or thinking of how to get them back on track through strategies, interventions or play-based programmes. This is a process known as normalisation in which we assume that all children’s development will essentially follow the same process. Our efforts then become focused on maintaining a typical and non-disabled pathway.

Over time, I began to question why children whose development differs from what we are told to expect are not represented within our contemporary understandings of child development. It seems contradictory to suggest that all children are unique and will develop at their own pace while measuring their development by the same standards or expectations. This set me off on a new way of learning about the diversity of child development and left me wondering:

If a child is autistic, does their autism only contribute to problems and delays? Or does being autistic mean that the developmental pathway will have different milestones?

If a child communicates in ways other than mouth words and conventional speaking, are other forms of communication not valid? Or should we learn about children's different communication identities and ensure this is represented in our understanding of child development?

If a child is physically disabled, does that mean we should presume less of their physical capabilities? Or should we explore how the environment is often disabling rather than the person’s competence in moving in a way that feels meaningful to them?

These curious questions made me realise there is a crucial opportunity as we move forward in understanding diverse child development. Although we are taught that there is a universal pathway that all children will follow, this is a myth. We will develop in infinite ways based on a whole myriad of factors. Our understanding of child development will expand when we open our minds to these possibilities.

Ways to expand:

Embrace divergent pathways of development.

One of the most significant shifts in my own practice was to embrace the fact that not all children are travelling down the same developmental pathway. Instead, children’s development can take off in lots of different directions because it is dynamic, vibrant and chaotic. Our role as educators is not to enforce a particular pathway; rather, we should ensure that we support and nurture what is developmentally meaningful to the child on that pathway. For example: if a typically developing child showed a particular interest or fascination for a type of play or topic, you would build upon this, and plan for it. The same approach should be taken for an autistic or ADHD child who has a special or intense interest, rather than to redirect or limit access to that interest.

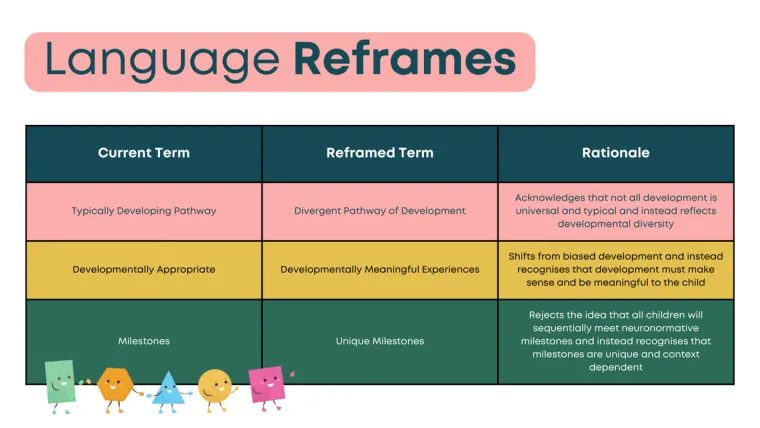

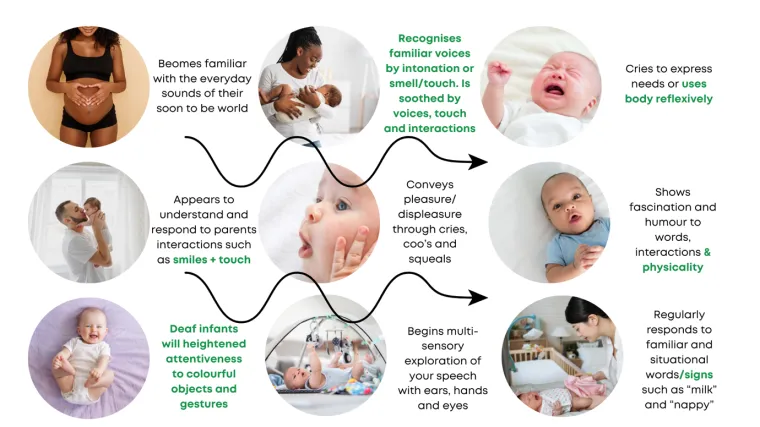

Green indicates the inclusion of divergent pathways for a D/deaf child.

Take a “more than one way” mentality.

Too much focus is placed on how a child with developmental differences and/or disabilities is not meeting a typically expected milestone. Still, thought needs to be given to the more than one way a child can demonstrate a particular milestone. For example, imagine you are caring for and educating a non-speaking Deaf child who efficiently uses British Sign Language. You would recognise that there is more than one way to communicate, and in this child’s case, they use sign language as effectively as someone who communicates through speech.

Learn about different developmental pathways.

If you were to conduct an internet search for autism, social communication differences, stammering, or sensory processing differences, your search would likely yield results that focused on how symptoms, problems, or issues characterise each of these lived experiences. The advice would also focus on fixing, reducing or eliminating the issues associated with these ways of existing. A deficit framework to human differences still dominates our education system, making it hard to learn about diverse development. This is gradually changing, and increasingly, we see theories and ideas emerge that tell a different story. Access training and guidance from disability-led and neurodivergent-led advocates and organisations which can offer a fundamental shift in how we define childhood.

Decolonise child development.

Like many, I have felt wedded to Piaget, Vygotsky, Maslow, Bowlby, and Bruner, and I have rarely questioned their pioneering insights. But over time, I have come to see that we exist within a sector that relies too heavily on white, Western, middle-class, male, non-disabled concepts of child development. This reliance reinforces a very limited knowledge base of child development that ignores the diversity of human differences and suggests a singular notion of childhood. The reality is that you are supporting and educating multiple childhood(s) which only sometimes submit to the same theoretical orientations. We can be grateful to these pioneers whilst recognising that they do not account for all descriptions of child development.

Know the child to teach the child.

I often notice that early childhood educators dismiss their personal knowledge of a child in favour of universal child development advice. For example, I recently supported a practitioner who noted that her key child got great joy from hand flapping and would often do this as a form of expression. She had also read that engaging in self-stimulating behaviours was not socially acceptable, so perhaps she should discourage the child. We spoke at length about the importance of trusting her knowledge of the individual children, especially as the stimming had a clear function. We also unpicked how problematic the term “socially acceptable” can be when spoken about in the context of children who have developmental differences and disabilities. Social acceptance should not be about fitting in but existing within a society that accepts and adjusts to differences.

Next steps

When engaging with early educators, I explain that there is so much yet to be understood in diverse development. At the moment, we don’t necessarily see this fully reflected in our child development guidance and documents. We, as educators, now have the opportunity to start building that knowledge base by capturing all the diverse ways that children can develop. Below is an example of this based on an increased understanding of interception, often referred to as our hidden sense, but one that is essential to our self-regulation.

Are there any aspects of child development that you have historically been told is an issue or a problem?

Using the template, conduct some research on neurodiversity in relation to that aspect.

Document what you have learnt and how you might apply this new understanding to practice.

Conclusion

While we can appreciate what has come before us, including pioneers, theories and descriptions of child development, we can also build anew as our understanding of diverse human differences expands. Not only will this make meaningful inclusion more possible, but it will also support educators to feel like they are truly making a difference to children’s lives in helping them to understand and affirm who they are rather than to deny them their neurodivergent and/or disabled identity.

References

This blog has been adapted and expanded upon from the upcoming book: Murphy, K (2024). Neurodiversity-Affirming Practices in Early Childhood: An Empowering Guide to Diverse Development and Play. Routledge.

Zhou, H., Gao, Q., Chen, W. and Wei, Q., 2022. Action understanding promoted by interoception in children: A developmental model. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, p.724677.

Burman, E., 2019. Child as method: implications for decolonising educational research. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 28(1), pp.4-26.

Connell, G. and McCarthy, C., 2013. A moving child is a learning child: How the body teaches the brain to think (birth to age 7). Free Spirit Publishing.

Early Years Evidence Store | EEF (educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk)